- Home

- Sylvia Atkinson

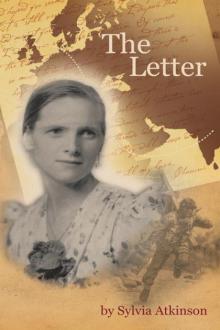

The Letter

The Letter Read online

The Letter

Sylvia Atkinson

AuthorHouse™

1663 Liberty Drive

Bloomington, IN 47403

www.authorhouse.com

Phone: 1-800-839-8640

© 2012 by Sylvia Atkinson. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the written permission of the author.

Published by AuthorHouse 02/08/2012

ISBN: 978-1-4678-8082-4 (sc)

ISBN: 978-1-4772-1487-9 (eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011963073

Because of the dynamic nature of the Internet, any web addresses or links contained in this book may have changed since publication and may no longer be valid. The views expressed in this work are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher, and the publisher hereby disclaims any responsibility for them.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

MAP

The Families

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Acknowledgements

Credit goes to Hilary Shields for introducing me to Tickhill Writers, and for painstakingly editing countless drafts of The Letter. I will forever remember her unstinting help and encouragement.

Nigel Wagstaff of Flight Line Graphics, who provided expert technical advice throughout, designed the map of India and saved the first draft when the computer and research materials were destroyed by floods.

I am honoured that Peter Archer, the war artist, has given permission for an extract from his painting, Go To It, to be incorporated into the book’s cover. I am delighted that his son, Ben Archer, designed it.

Peter Archer’s original work, depicting my father Corporal Thomas Waters M.M. laying the land line across Pegasus Bridge on D-Day 1944, hangs in the officers’ mess of the Royal Corps of Signals regiment at Blandford Forum, Dorset.

Many thanks go to the Royal Corps of Signals Museum at Blandford Forum Dorset for housing my father’s medals, archive and an exhibition of his action on Pegasus Bridge. Also to Colonel Robin Pickering (retired), for the research on Thomas Waters M.M.

I owe the deepest thanks to my wonderful parents whose dignified courage has inspired my life. Also to my Indian family and everyone at home who have helped me to write this book, especially my husband. Without his love and unwavering support I would have given up long ago. It is to them that this book is dedicated.

Author’s Note

The Letter is based on the fictionalized lives of my parents, who overcame disadvantage, race, war and disability. The historical events in India, Burma, China and France during World War Two are intended to be accurate. It is worth stressing that I have changed some names, imagined characters, compressed action and invented places in line with my story.

MAP

The Families

The Scots

Margaret Riley (Maggie/ Charuni)

Mr and Mrs Riley

Margaret’s parents

Nan

Margaret’s eldest sister

Jean

Margaret’s favourite sister

Mary

Margaret’s youngest sister

Con

Margaret’s brother

John (Johnny)

Margaret’s brother

Willie

Mary’s husband

David (Davey)

Nan’s husband

Sheila

Nan’s daughter

The Indians

Ben Atrey (Vidyaaranya) Margaret’s first husband

Pavia Margaret and Ben’s daughter

Saurabh Margaret and Ben’s eldest son

Rajeev Margaret and Ben’s youngest son

Dadi Ben’s mother

Vartika Ben’s eldest sister

Suleka Ben’s youngest sister

Hiten Vartika’s husband

Anil Pavia’s son

Muni Margaret’s maid

The English

Tommy Waters Margaret’s second husband

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Tommy and Margaret’s daughter

James Elizabeth’s husband

Albert Waters Tommy’s father

Shirley Waters Tommy’s stepmother, Albert’s wife

Alice Tommy’s eldest sister

Florrie Tommy’s youngest sister

Matt Florrie’s husband

Chapter 1

Yorkshire 1985

Margaret’s small fireside table was covered with the usual clutter of books, writing materials and the buff envelopes of bills, but the blue airmail letter tucked in among them threatened to cause havoc. A long forgotten nightmare returned disturbing her sound sleep. She was in an unfamiliar house. Corridors lengthened, changing shape while she frantically raced down them; open doors of countless rooms slammed in her face. Suddenly she was spinning, falling headlong down a black tunnel periodically lit by crashing lightning. Illuminated figures of children beckoned, urging her to come to them. She reached this way and that, frenziedly trying to catch them but they vanished whenever she drew near. Last night was the worst. The three elusive sprites danced closer and closer… She saw their eyeless faces…

Jolted awake, she got up and made a cup of tea. If only she had someone to talk to. For years her daughter Elizabeth had tried to persuade her to have a telephone installed so they could be in touch every day, especially in an emergency, but this wasn’t an emergency. Not like the time she fell and was found by Peggy, a neighbour. The dizzy turn resulted in a trip to

hospital and three stitches where Margaret’s head hit the kitchen table. A subsequent appointment was arranged. She went with Elizabeth. The consultant said the fall was caused by the vagaries of old age, possibly a minor stroke, and recommended wearing a surgical collar, taking aspirin daily and regular check ups. Elizabeth insisted she wore the contraption. Margaret felt trussed up like a dead chicken.

The phone was different. Elizabeth and her husband James offered to pay for everything including future bills. Some of Margaret’s friends chatted for hours but it always seemed so impersonal. A convenient phone call was no substitute for a sit down visit, and besides she didn’t want to be instantly accessible. She liked things the way they were but was hurt when Elizabeth said she was unreasonable. Anyway it wouldn’t be any use. How could she talk to anyone about the letter… especially on the phone? Yet Elizabeth would have to know… What would she think?

If Margaret didn’t get a move on she’d be late for mass, but she was in such a muddle scrabbling through drawers and bags to find her purse. Thoroughly cross, she pushed a few coins in the Offertory envelope, threw a shovel of slack on the fire, checked she’d locked the front door three times, pulled the handle upwards on the back door to catch the lock and turned the key.

In the Sunday spring sunshine bold daffodils triumphed beneath the straggling privet hedge bordering the untidy lawn. The flash of yellow lifted her mood while she waited on the pavement for the customary late church bus to lumber round the corner. The patient driver banished the Sunday scrubbed boys from her reserved front seat, sending them down the bus. It was the same every Sunday but this one was potentially like no other and she wanted to get it over.

The smell of burning candles, heady incense, hymn singing children and the soft Irish brogue of the priest saying mass went some way to restoring Margaret’s equilibrium. Reluctant to leave the church, she knelt and lit an extra candle in the side chapel by the serene flower-ringed statue of the Blessed Virgin. Although she went to mass on the bus one of the family always collected her. She could picture James, her son-in-law, reading his paper in the car. He wouldn’t come in, said it wasn’t his thing. Her daughter Elizabeth came at Christmas but the three of them spent most Sundays together.

James shrugged off Margaret’s nod of an apology for keeping him waiting, resigned to her greeting people for as long as it took. He noticed she looked tired, her quick smile a little forced. He’d mention it to Lizzie.

At lunch the food stuck in Margaret’s throat. She drank copious glasses of water to swill it down. Elizabeth asked if she was all right. “It’s nothing. I slept badly. I think it’s the start of a cold.” James advised putting more whiskey in her cocoa, expecting a witty reply, but she hardly dared look at him across the table. She wanted to shout, “Stop! I’ve something important to say,” but the words dried in her mouth.

She usually dozed in the lounge to the comforting scraping of plates, rattle of glasses and muffled voices of her daughter and son-in-law drifting in from the kitchen. Today she couldn’t settle. Her stiff fingers fumbled with the Velcro fastening of the blasted surgical collar. Released, she threw the offending article on the floor and sank back in the cushioned armchair snapping her eyes shut. It was no good. She simply couldn’t carry on like this. Fidgeting with the corner of her pretty blue cardigan she opened her eyes at the crunching of feet on the gravel drive. Through the tall window she caught sight of James going out, being pulled along by Rory, his boisterous setter. This was the chance to end weeks of indecision. She called, “Come, Elizabeth, take the weight off your feet for a few minutes.”

Elizabeth carried on methodically filling the dishwasher. She thought it remarkable that her mother’s cultured Edinburgh accent was as strong as ever, even though she hadn’t lived there for more than fifty years. The call came again, this time louder, and more insistent. A rare occurrence, but the tone was a command, with possibly a reprimand at the end of it. Elizabeth dried her hands muttering, “I’m not a child… It had better be important.”

Margaret’s frail figure housed an iron will, but tense and uncertain where to begin, she imperiously indicated the matching sofas. Elizabeth obediently sat on the edge of the nearest, “Mum, you know I always finish in the kitchen before I sit down.”

“Elizabeth, some things are more important than a tidy kitchen! Besides I want to talk to you without James.”

“Without James… ?”

Allowing no further opportunity to query the unusual request Margaret continued, “I want you to know that I was married before… I mean before I met your father.”

Relieved that the intensity in her mother’s blue eyes was not the forerunner of bad news, Elizabeth said lightly, “Oh is that all? I know you were.”

Astonished, Margaret exclaimed, “Who told you?”

“You did… years ago when I was nine.”

One dark winter afternoon, leaving her mother reading and shivering by the fire, Elizabeth had crept upstairs and sneakily opened the fitted cupboard in the spare bedroom. It was crammed with feather pillows, sheets, blankets, bed spreads, towels, and other just-in-case household commodities. There were at least two of everything, nothing was thrown away. She was foraging through when she came across some unfamiliar khaki cloth and cardboard suitcases.

Getting them out quietly without something falling and alerting her mother had not been easy. She surreptitiously dragged them to the window to read the remnants of their glued and tattered labels. The spidery handwriting held snippets of names and destinations, a world of grown up secrets waiting to be solved.

When Elizabeth opened the cases there was a strange smell, not unpleasant but different, rich and earthy, evocative of strawberries and warm summers spent out of doors. She warmed her hands by running them over the stored deep velvet, green, gold and blue silk. Some of the fabric was embroidered with gold dragons, blue and pink birds. She draped this over the big double bed to catch the fleeting half-light but her favourite treasure was a creamy silk kimono. The front was plain but the back was covered with red chrysanthemums, intertwined with delicate green leaves, flowing down to the hem, contrasting with the dull-brown linoleum floor. Queen of the Orient, she preened in front of the three mirrored dressing table.

“ . . . It was the day you caught me emptying the old suitcases. I thought you’d be cross because I was dressed in your kimono trying to fathom out the engraving on some discoloured bracelet.”

“I do remember. It was my identity bracelet?”

“Yes, you said it was from the war. It read Margaret Riley Atrey. I knew grandpa’s name was Riley but I didn’t recognise the other name so I asked you. You told me Atrey was the name of your first husband. The only thing that bothered me was who my father was. You said that he was the man I’d always known. I was so relieved because for ages I’d been thinking I was adopted.”

“You were a funny little thing, always wanting to know more than was good for you. My first husband was Indian so he couldn’t have been your father.” Margaret’s chest tightened. She hadn’t meant it to come out like that. She glanced fearfully at her daughter, “ . . . you don’t seem surprised?”

“That you were married to an Indian? India has been part of my life for as long as I can remember. You told me the kind of things you can only know if you’ve lived among the people. Other children’s mothers got flu. You got malaria. Me and dad piled eiderdowns and blankets on top of you and gave you lots of drinks out of a special cup with a spout. When I kissed you goodnight you were all clammy. I asked dad if you’d die but he said you’d get better. So that made it okay. What really scared me were the Indian hawkers. You know the ones with legs like matchsticks who came to the back door selling cardigans out of suitcases. They spoke loudly waving their arms and nodding. You nodded back, speaking louder in some funny language. I hid under the kitchen table ’til they’d gone.”

“Oh Elizabeth

, we were only talking.”

“But Mum you’d told me stories about brave warriors who didn’t cut their hair and wore it rolled up under a turban. They carried curved daggers which, once drawn, couldn’t be sheathed unless they spilt blood. I was convinced I’d be murdered and had awful dreams about being kidnapped and squashed in one of their suitcases.” Elizabeth melodramatically embellished her tale, “Trapped, blinded by the colour of sweaters and cardigans, suffocated by the smell of wool…”

“My word Elizabeth, I had no idea! You always had a vivid imagination. I can’t believe all that went on in your head.”

“I liked it really, so no, I’m not surprised.”

Margaret was tempted to leave it there, secure in Elizabeth’s childhood memories, but she couldn’t deny the past that roared in her ears. “Do you remember the photograph album in the green cover that I kept in the top of my wardrobe?”

“You mean the India album. The pages were separated with tissue paper and there were pictures of your friends, menus and birthday cards decorated with lace and tiny ribbons.”

“Yes and a small black and white photograph of a little girl in the snow.”

“Mmm… a man was standing near holding the reins of two black horses. I didn’t know it snowed in India until I saw that.”

“You remember so much.”

“Of course I do. The girl was your friend’s daughter and…”

“She was mine… Is mine… Her name is Pavia.” Margaret repeated the name, savouring the shape of the tumbling letters, fighting back the tears. “I also had two sons, Saurabh and Rajeev.”

The Letter

The Letter