- Home

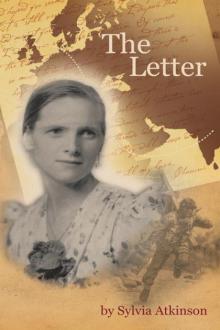

- Sylvia Atkinson

The Letter Page 2

The Letter Read online

Page 2

Elizabeth took hold of her mother’s hands, “Why are you telling me this now?”

Margaret started to explain, “Because I’ve had a letter…”

“A letter… ?”

Gripping her daughter’s hands like lifelines Margaret said, “Yes, from India and…”

The dog barked. James was coming up the drive. “Elizabeth, please don’t say anything about it to James now. It’s getting late. Tell him in your own way when he comes back from taking me home.”

Chapter 2

Elizabeth cuddled into James’s back. In the busy week sometimes the only chance they had to talk to each other was in bed. Snuggling at weekends led to other things. James said sleepily, “You do know it’s Sunday?”

Elizabeth nuzzled his ear. “Did you know mum was married before she met my dad?”

“God Lizzie you picked a fine time to tell me.”

“To tell you the truth I sort of forgot about it.” She divulged her mother’s secret. Instantly wide awake James said, “Didn’t you suspect there were children?”

“No I didn’t give it a thought.”

“How did they contact her?”

“Through a letter…”

“And…”

“I don’t know the details.”

“Didn’t you ask?”

“You came back, and Mum didn’t want to talk about it in front of you.”

“Why not?”

“I think she was frightened.”

“Frightened of me! I’ve always been there for her.” Lizzie leant towards him. “It’s no use kissing your way out of it.”

“I’m just saying sorry, I didn’t put it very well. I meant she was afraid you’d disapprove.”

James lay back and stretched his arms over his head, “I thought she wasn’t herself today, too quiet by far.”

“It’s the quickest Sunday lunch we’ve had without you two arguing. Politics and religion, you’ll not change her views.”

“Scottie and I don’t argue. We discuss.” Early in his marriage to Elizabeth, mellowed with whiskey, James tried to get Margaret to decide what he should call her. ‘Mother-in-law’ was too formal. He wanted something more affectionate. She thought about it and said he could call her Scottie. It was a nickname from when she was young. James thought it must have been at a time when she was happy because she had a far away look when she suggested it.

* * * * *

Margaret spent the week worrying. She thought she knew James but she’d been the victim of prejudice from the most unlikely quarters. The following Sunday she was relieved to see his silver Mercedes outside church. She was expecting some reference to last week’s conversation but he was his good-natured self. Maybe he didn’t know? What if she had to tell him?

The journey took an age: every traffic light on red; a police car on the straight stretch where there was an accident. James put his foot down on the motorway but lunch was already on the table when they arrived. Elizabeth filled any gaps in the conversation, offering to drive her mother home so James could have an extra glass of wine. Margaret was becoming more agitated by the minute. Knife and fork in hand James said, “Well you’re a dark horse, Scottie. There’s certainly more to you than meets the eye.”

Elizabeth glared at her husband. Trust him. She thought they’d agreed to wait until her mother brought the subject up. Margaret was glad of the opening. She had a speech prepared, the bones of which she had rehearsed again and again during the sleepless nights of the previous week.

“James, I assume from that remark you are referring to my previous marriage…”

“But,” James interrupted, “how on earth did they find you after all these years?”

“One of my grandchildren traced me. His name is Anil. He is the youngest son of Pavia, Elizabeth’s Indian sister.”

James wasn’t interested in who was related to whom. He wanted to know the big picture.

Margaret began easily enough, “My first husband, Ben, was staying with our daughter Pavia at her home in Lucknow. During his visit Anil asked his grandfather questions about the family. Ben revealed that I had not died as the children believed but had been forced to return to Scotland. He produced a letter that I had written to him when we were university students. Apparently it was his habit to carry this, as a kind of good luck charm. Anil traced me from the address.”

“It’s absolutely incredible Scottie! Who on earth would keep a letter for over…”

“Fifty three years… The address was that of my parents’ house but luckily the local postman recognised the surname and took it to my brother John, who still lives nearby. He forwarded the letter to me unopened.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?” Elizabeth said, upset by her mother’s lack of trust.

“I wasn’t certain whether to reply. I didn’t know if I could stand the disruption.”

“What do you mean disruption? Mum if there’s any disruption it’ll be caused by your secrecy.”

“Elizabeth, you don’t know what you’re talking about. Custom dictated that I wrote to Ben asking for his permission to contact our eldest son Saurabh. I couldn’t do it so I sent a short note to Anil, thanking him for writing and giving him my correct address. Saurabh’s first letter arrived before I had made up my mind whether or not to write to his father.”

“Oh I see.” Elizabeth said.

“But you’re not angry?”

“Far from it… I’m thrilled. I’ve got a million questions.” A million answers Margaret didn’t want to give. “How old are they? Obviously older than me…”

“Yes, Saurabh is ten years older and a high ranking Indian Army officer. He recently organised an All India Hockey Tournament in honour of his dead mother, and here I am alive and kicking!” But Margaret’s humorous remark was at odds with the sorrow and anger stirring inside her and she couldn’t go on to give the birthdays of her other children.

As early as Elizabeth could remember, what ever the cause, her mother insisted that family business was not discussed outside the home. How would she deal with this? If the Indian children were to be reunited with their mother it would have to be handled sensitively.

James had no such qualms, “You know the old saying, ‘Only the good die young.’ Well you’ve got no chance, Scottie! You’ll last forever. Joking apart, if you want to go to India, we’ll take you.”

“James!”

“Don’t be cross, Elizabeth.” Margaret said in his defence. “I know James means well but I’m in my seventies. My health won’t allow me to make the journey. I don’t want to die in India.”

“You won’t die. India gets thousand of tourists every year. We’d be with you… It’s not as if you’d be among strangers.”

Margaret declared forcefully, “I mean it. It’s out of the question.” James wisely backed off from any more discussion on the topic.

Elizabeth had always wanted a brother and now she’d got two. An older sister was different, that would take more getting used to. What could her mother possibly be afraid of? Disappointed there’d be no trip to India she sought some kind of compromise. “Mum, will you let me write to Saurabh?”

Margaret didn’t want to hang her life out to be scrutinised, especially by her children. She had almost dropped her guard last year, while watching Jewel in the Crown on television. The programme, screened on Sundays, was set in India during the time she lived there. It went on for weeks and was compulsive viewing for Elizabeth. Margaret pretended to enjoy it, and in a way she did, but it brought back bitter sweet memories that she couldn’t share with her daughter.

“Scottie…” James said, fired up with the whole idea of an Indian connection, “letters would be a way of introducing your children to each other. You never know they might get on.”

Margaret hadn’t thought

of it like that and before James drove her home she agreed that Elizabeth would write to Saurabh.

Chapter 3

Margaret switched on the radio, habitually tuned to radio four, ate her breakfast, washed the dishes and tidied the kitchen, but avoided picking up the airmail letter lying stranded on the sisal mat by the front door. It was absurd. She’d have to open it some time. Where was the scissor gadget James had bought to pick up the post and minimise the chance of her toppling over? Elizabeth said to put it in the same place each time she used it, but doing as she was told was not Margaret’s strong point. She found the contraption disguised by the jumble of coats hanging in the hall, expertly flipped over the envelope and retrieved it from the mat.

Clearly printed on the back in a flamboyant hand was Colonel Saurabh Atrey, V.C., V.S.M., India. Sitting safely in her fireside chair Margaret’s hand trembled as she tore open the envelope and removed two letters.

My Dearest Mama

My father was with me when your reply came. He is seventy-eight years old now. I wish you could have seen the glow on his face when he heard that you are alive and fine. After adjusting his spectacles he read it again and again. He asked me to wish you to come to India to be with all of us. We were helpless to find the truth as children. We accepted what the adults said, but I used to weep alone for Mama. A warrior who’s not afraid of death I used to weep like a child at night over a pillow. This letter of yours is my most precious possession. I read it again and again. Long stories we will tell when we meet as surely we must.

She read the letter over and over memorizing every word; crying for the tousled headed boy grown into a brave soldier who could so easily have been killed without her knowing.

What could Saurabh mean by writing that his father requested her come to India? It was inconceivable that she would return to where once, naively happy, she had been plunged into desperation and despair. Yet she was disconcerted by faint murmurings of disappointment that there was no letter from Ben. She could scarcely believe he was seventy-eight years old but Margaret often forgot that she was seventy-two. Their love was a lifetime away. Pavia’s enclosed letter drew more tears and self-recrimination.

. . . Papa said you had gone back to your father in Scotland. We couldn’t believe that you would leave without kissing us and clung to each other. Your jewels and clothes were in your room waiting for your return. For a long time Saurabh pestered my father until he told us that the ship on which you were travelling had been torpedoed. Then it was useless to ask.

As a child the days sped past but when I was being married and having my own children I felt the loss of you most keenly. Of course my aunts, brothers and father were with me when I married Kailash. He has turned out to be a devoted husband and I am very fortunate to be married to such a good, kind man. He continued educating me, encouraging me to take my degree before we had our family but it is at those special times when you need your own mother. I had so many memories of you. I wanted you beside me at the most important times of my life.

To tell you the truth mama I am not as beautiful as I was as a child. I have put on a lot of weight since becoming a mother and grandmother . . .

The fair skinned, slender girl with eyes that would melt any heart was a grandmother. They had both learned to live with an emptiness that the years couldn’t take away. Happy family photographs confirmed how much Margaret had missed. Her daughter was blessed with three children, two of them married with families. Margaret was not only a grandmother but a great grandmother. Saurabh had four unmarried children. The years had gone and there was no way she could recapture them.

She had news of her youngest son Rajeev from Pavia and Saurabh. His promotion to Brigadier, happy marriage and two sons was more than she could hope for. She wouldn’t blame him if he didn’t contact her. He had been such a sickly crying little one. How could she have left him, left them all? Things happened in such a hurry but that had been an excuse; acknowledging it made her feel worse.

The afternoon post arrived and with it came Rajeev’s poignant letter, breaking through Margaret’s remaining defences.

Dearest darling Mama,

I got your letter sent to me through Saurabh. You do not know how thrilled I was first on knowing about your being there in England. It is a miracle for me. I had never thought of knowing your existence. No one had spoken about you to me. All these years and I was made to understand that you are no more. No body was able to explain about your absence except when someone did speak it was such a hush hush affair.

You can imagine how one feels on knowing the mother who has given birth to you has suddenly gone from your life to reappear again . . .

It is as if we have found a lost treasure. I think I cannot explain the feeling. We all want you to come and stay with us. You do not know what a void your absence from our life has created.

Do write or phone so we can speak

The longing to be with her children, so long submerged in the business of everyday living, was brought dangerously to life. They shared loneliness at the core of their being. Could they really forgive her? Could she forgive herself?

Margaret thought of her own loving mother and the happy family home in Queensferry where she was born and spent her earliest days. Their house was tall with a slate roof, hemmed in by other buildings, a higgledy-piggledy grey row overlooking the water. Standing on tiptoe, balanced against the window ledge she could see the gulls wheeling and cawing above the waves and the trains thundering across the Forth Bridge where her father worked on the railway. Where had the trains come from; filled with imagined people, where were they going? Margaret was slow to forgive her parents for leaving the sea when her father’s work forced them to move.

Gorebridge, inland with its narrow twisting main road and linear sprawl of houses dripping into the valley, was a disappointment. Margaret’s eldest sister Nan was away in service but the house was crowded with her parents, two older brothers, and two younger sisters. There was less than a year between herself and her sister Jean making them more like twins. Always together, they escaped from the confines of the house onto the hills; scrambling up the rough grassy slopes, avoiding prickly green and yellow gorse, flattening the tall bracken until, hot and panting, they reached the top.

It was forever summer. High above the village the subtle green shades of patterned flat fields sprawled out below them. On a clear day, in the distance, Margaret could see her beloved Firth of Forth and way beyond the water the blue-grey shadows of far away hills. One day she’d travel to those distant sights and discover the fascinating places in her school books.

Racing Jean down the hill with her arms flung wide, the wind billowing up through her cardigan Margaret soared high in the sky, riding on thermal currents like an eagle looking down at the world only to crash to earth. The sand paper grit of the hillside gouged red channels in her bare legs. Scarlet cheeked and bleeding she limped home to be cleaned up by her mother who scolded with every wipe that Maggie would be the death of her.

Margaret stirred the coals of the late afternoon fire, spinning flames in the black grate, reminiscent of the lights of halls where she sang and recited the works of Robert Burns, basking in the audience’s applause, winning prize after prize. She was the first person in her family, and from the village, to win a bursary to study at Edinburgh University. She wondered what her parents would have given for such an opportunity. Through her their future held so much promise. Cursed with a restless search for transitory excitement and adventure she hadn’t given them a thought.

She vacuumed the downstairs rooms and made a pan of mince and onion. No one came to visit, and she didn’t feel like going out. By evening she couldn’t be bothered to cook potatoes to go with the mince. She had a tin of tomato soup and soft white bread on a tray by the television while she watched the news, clearing away before Coronation Street. There was nothing else worth watching so sh

e switched it off. She’d begun a letter to Jean but couldn’t get on with it so read for a while, filling in time, trying to put aside her guilt and heavy heart.

At ten she drank her bed-time cocoa, wound the clock and pulled the metal spark guard round the hearth. She was ready for the succour of a hot water bottled bed and the smooth black rosary beads ever present under the pillow.

SCOTLAND 1931-1935

Chapter 4

Scotland 1931

Ghosts from the past crowded Margaret’s dreams transporting her to their former world where youth was reborn. University life was hectic and she was already making a reputation with the fashionable Edinburgh literary set. Every topic was up for debate and a dozen people ready to discuss it, often well into to the night. She was glad to be able to dash home to the backwater of Gorebridge for the occasional weekend. There she could sleep late and didn’t have to argue the finer points of anything. She left it to the last minute to leave, for there was Mass to go to, dinner to eat and the company of her brothers and youngest sister Mary.

One Sunday evening the Edinburgh train was already standing in the station when Margaret reached the booking hall. Ticket in hand, she ran along the platform peering into crowded compartments. She had reached the last before finding the possibility of a seat. Pulling open the tightly closed door, she clambered over the occupants, apologising in all directions, ignoring the shuffling of newspapers and squeezed in amidst irritated tutting.

The young man sitting opposite smiled as if the scene he had witnessed was a huge joke. Margaret automatically smiled back. For a while they silently shared their amusement grinning at each other. His thick ebony hair fell onto his forehead and his black-brown eyes danced invitingly. She was making eyes at a foreigner, in a carriage filled with pale Scots and she couldn’t stop. He spoke formally, introducing himself, “My name is Vidyaaranya Atrey. I am a medical student at the university.”

The Letter

The Letter